Recently I've put together a python project that tests Elo matchmaking in a simulated environment. Elo matchmakers, for those unfamiliar, are used in competitive games like chess. They can choose which players are matched, and by observing who wins or loses, estimate each player's skill level. These systems suffer a common complaint: players grind hundreds of games and barely budge the matchmaker's estimates. Is the matchmaker to blame? Can Elo systems really misplace people badly, and are they vulnerable to 'Elo Hell' - persistant bands of players with closely estimated skills, but widely disparate true skills, making for random and frustrating matches - or are these complaints another example of Dunning–Kruger syndrome?

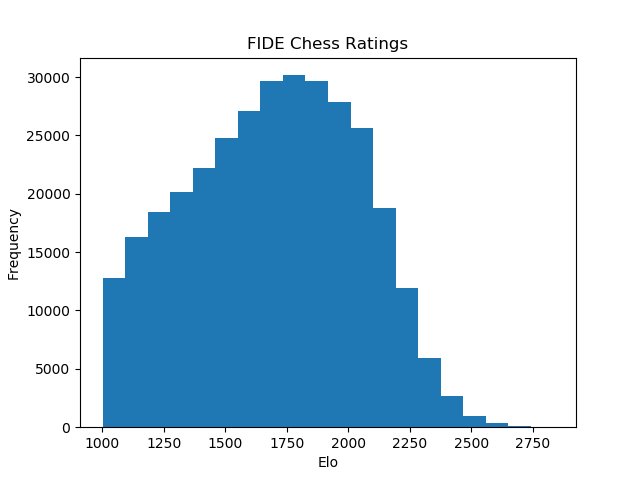

To test this, I went to FIDE, who helpfully have a public database of all professional chess player's Elo ratings. Although FIDE puts a hard floor on all rankings, using numpy we can create a randomized distribution that roughly mimics the actual score distribution. These will be our players' true scores.

Next, we can initialize our estimated rankings by setting all players to the same rank (here 1690, the median chess ranking). All that's left is to have players match against each other in an initial free-for-all.

import EloSim as e

# generate players with a randomized true-skill distribution

players = e.initplayers()

# Have players match against each other to estimate rank. Because all players are initialized with the same estimated Elo, we should match freely without skill-brackets

playtournament(players, team_size=1, uncertainty=32, learning_rate=1.0, rounds=20, usebrackets=False)

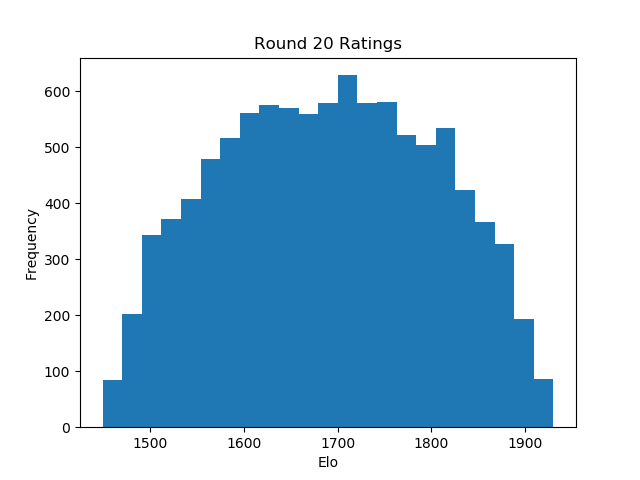

And the player base is initialized! We can see the estimated skill distribution take shape within 20 rounds of play.

With a rough estimate of player skills, we can now start making educated matches, where players of similarly estimated skill can face each other. We will bucket players into 23 skill brackets (as is common in most chess tournaments), allowing for some play outside the brackets.

# Play a 100 round tournament where players are roughly matched according to their skill level

play_tournament(players, team_size=1, uncertainty=32, learning_rate=0.995, rounds=100, usebrackets=True)

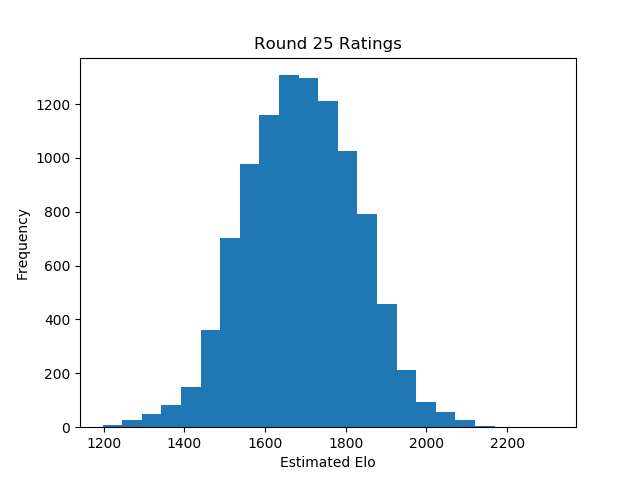

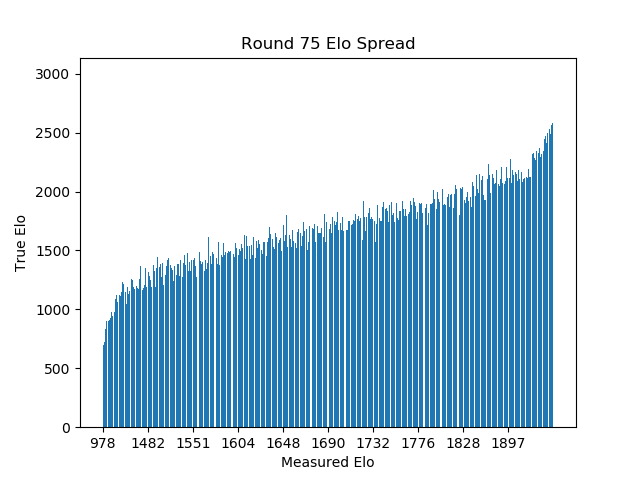

We quickly see our distribution tighten to match a Guassian approximation of the actual of FIDE ratings.

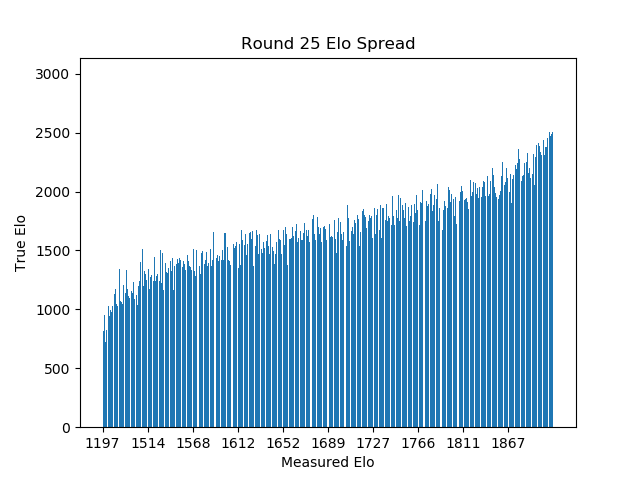

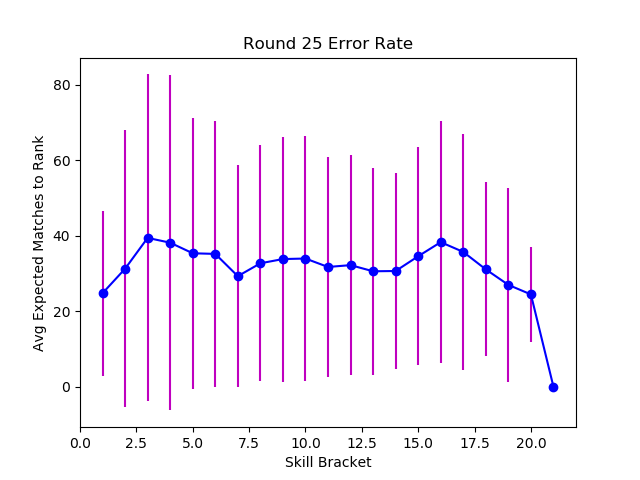

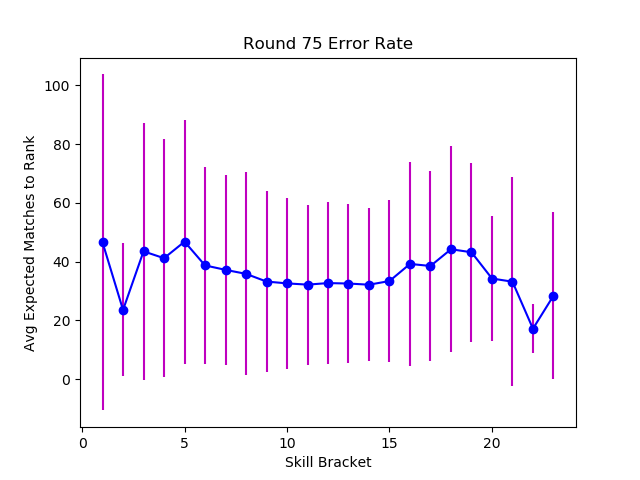

To measure our prediction accuracy, we will look at the overall skill spread, and at the number of matches it would take to move players from their estimated ranked ordering to their true ranked ordering.

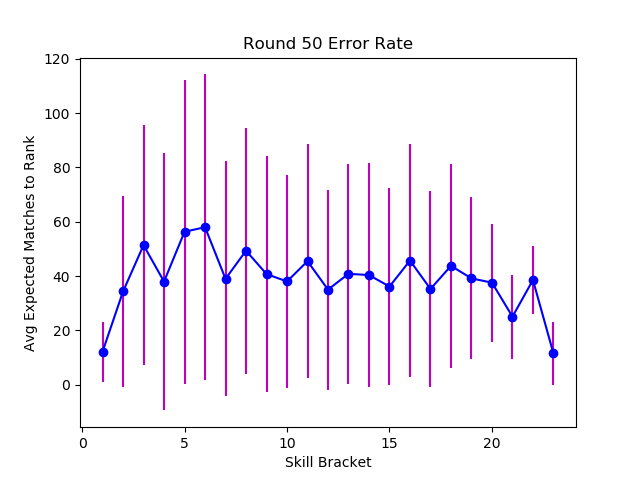

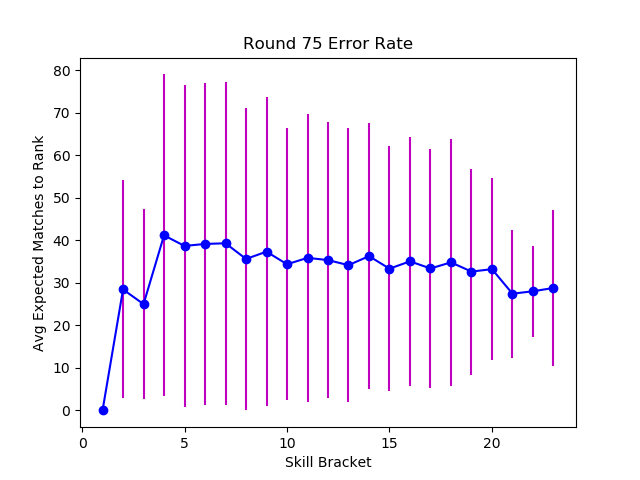

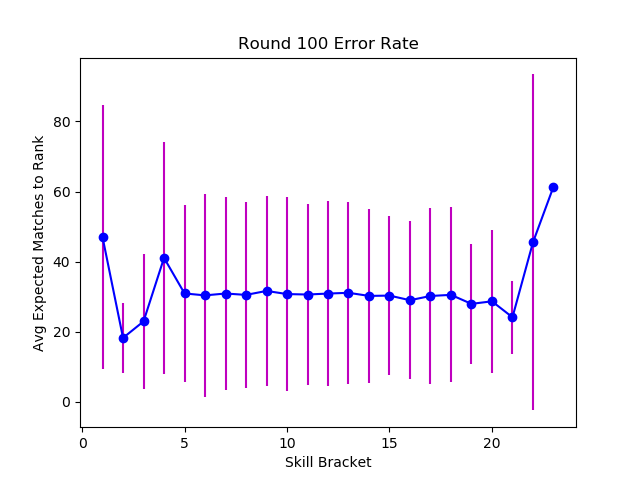

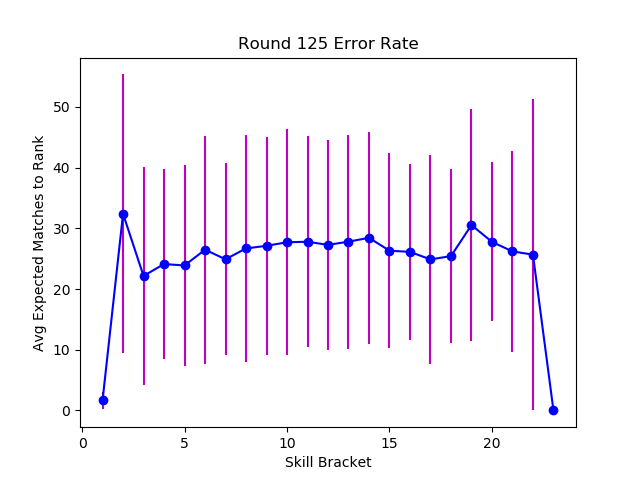

Below we can see that the tournament from before yielded roughly accurate player rankings, with a moderate but persistent margin of error across all skill levels. Even in seperate tests where I expanded the team size to 5 person teams (used in online games like League of Legends and Overwatch), the results were not significantly different. Error margins were moderate and persistent across all skill bands, with the greatest fluctuations at the tails of the distribution where players are sparse.

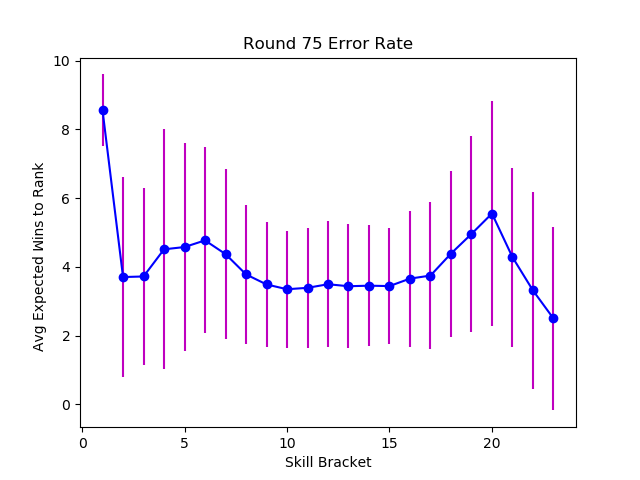

There is an insidious detail of getting to one's true rank. Although players average about 30 matches from their true ranked order, the number of consecutive wins or losses it would take is much lower, around 4. While four consecutive wins is unlikely against similarly skilled opposition, this isn't always intuitive. Slot machines take advantage of this by frequently showing an off-by-one Jackpot miss, convincing players that a big payout is likely. Elo systems that have strong bracketing with prestigious ranks, or that display points won or lost after a match, are probably similarly addictive. This might explain the frustrated players who see their easy expectations meet hard reality.

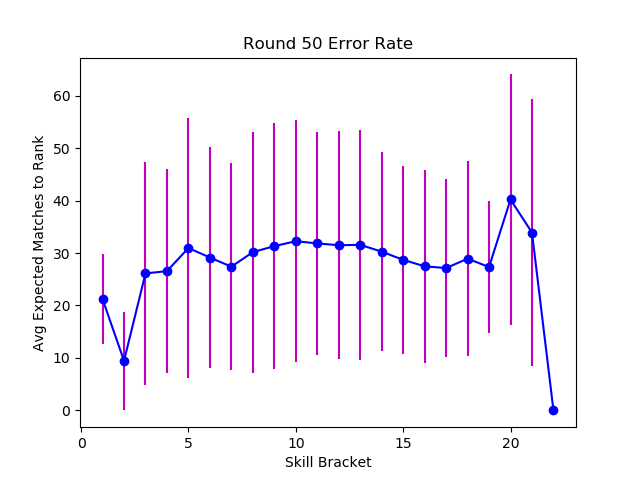

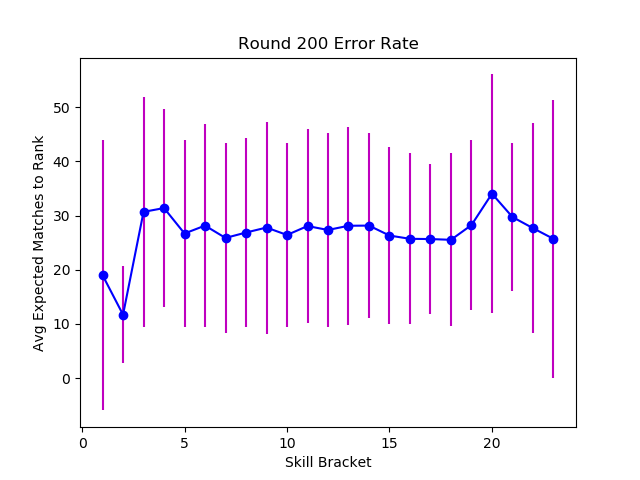

So far we've used wide matchmaking bands, matching players with anyone within 435 (10000 players / 23 bands) places in the sorted ranking. Let's switch to a stricter match-maker that attempts to pair players within tighter bands.

While tighter matching will initially have a wider skill spread and more randomness, it eventually converges to a narrower error variance than the more randomized matchmaking. Tuning the learning rate and uncertainty has a similar effect - making extreme (good and bad) luck streaks less impactful, and making the system converge toward lower error margins and lower variance.

# Play 200 rounds with tight matching and gradually narrowing uncertainty

play_tournament(players, team_size=1, uncertainty=50, learning_rate=0.988, rounds=200, match_rnd=0.0, usebrackets=True)

After about 125 matches, plus the initial 20, the matchmaker is no longer improving it's accuracy.

So what have we learned? Elo systems are roughly accurate, and tighter matchmaking and smaller point rewards can modestly improve accuracy. Adapting an Elo model to a specific game lets you add in extra parameters to improve accruacy. FiveThirtyEight uses Elo systems to rank NBA and NFL teams, adding in a home court advantage that adds a small bonus to a defending team's Elo score. It's also common to add performance bonuses, where players and teams that win by a large margin get more points. On the other hand, factors like skill decline, sloppy league matchmaking, roster changes, and rule changes all add randomness and decrease model accuracy.

Importantly, even in well-tuned Elo systems most players will grind hundreds of games with little measured change. Oddly, this is a feature as much as a bug. If the model is roughly accurate, large changes aren't needed. Things only become bad when we consider the addictive sides of Elo systems - the tantalizingly small number of wins to advance to the coveted, elite ranks. Games that emphasize this may be expanding and tormenting their player base in equal measure.